Other Worlds

What is Tabletop roleplay?

What is Tabletop roleplay? For many people, tabletop roleplay begins and ends with the behemoth of this scene, Dungeons and Dragons. But fundamentally it is a technology, or a technique. A way of collectively imagining a place through shared suspension of disbelief, a vision shared through words and occasional pictures, that gains an intense solidity through mutual consent.

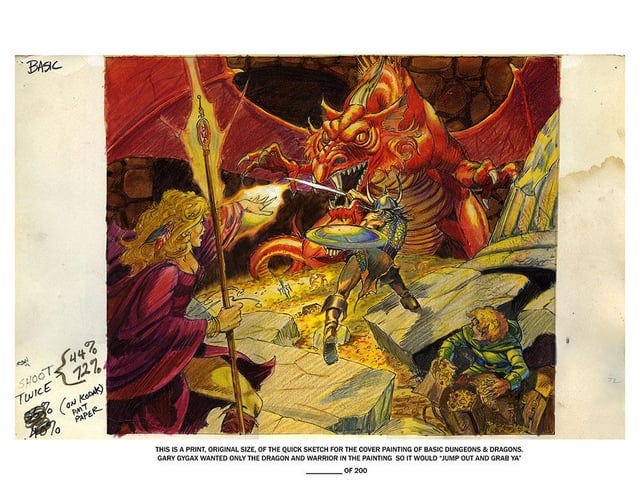

(An initial sketch for the cover of the D&D Red box by Larry Elmore)

Imagine a room. It’s cold and dark. Very dark. But there’s flickering light coming from a crack at bottom of a door. There’s a sudden knock at the door. What do you do?

With words, we’ve created a space together. There are hundreds of possibilities for what you could do. You could try to hide in a corner. You could open the door. You could ask what they want. You could scream. Anything that could be imagined, and seems consistent with the world we’re creating together, would be allowed to be suggested. Once agreed on by the table, that action becomes part of our shared world. It is an active process. It is Worlding.

Worlding is a term opposed to worldbuilding. Worldbuilding has connotations of imposing a structure on something, of creating a static lore, a static set of realities. Worlding is an active process, always in the act of happening, a process of giving meaning to the world through experiencing it. As the philosopher Heidegger says:

“[There is]…the wonder that this world is worlding around us at all, that there are beings rather than nothing, that things are and we ourselves are in their midst, that we ourselves are and yet barely know who we are, and barely know that we do not know all this.”

We are in a constant state of making the world. And Tabletop roleplay plays with this, lets us roll with this possibility, let’s us form worlds together through action and reaction, through a mutually bound imagining.

I discovered roleplay when I was around 10. Obviously I had played make-believe before, but there was something compellingly different about this possibility. I think it was the combination of a solid set of rules to play within, and a world to explore. But a large part of the lure was the feeling of agency, the feeling that I could make a difference in this world, that I had control over an avatar’s actions.

Of course, many of the bounds within that system I gradually found to be problematic. Gary Gygax, part-creator of the D&D system, was a biological determinist and had Manichaean tendencies, so that belief system underpinned the mechanics he devised. And when I started wanting to use something like D&D for an art project, I was struck by how embedded this was. As Donna Haraway says in Staying with the trouble:

"It matters what matters we use to think other matters with; it matters what stories we tell to tell other stories with; it matters what knots knot knots, what thoughts think thoughts, what descriptions describe descriptions, what ties tie ties."

So I set about looking for other ways to create that same shared imaginative space. I tried creating a new system, which brings its own issues, but then realised that 100s of people had tried to do the same thing, and that many of those attempts had undergone a lot of playtesting over the years, and were also open source. There is a culture within the scene of taking mechanics from a plethora of places to make a new combination that matches the space that you are trying to create.

Table top roleplay games, or TTRPGs as they’re often known, are both an analogue technology, a way of using language to create a shared interactive experience, and a worldwide culture that has been developing for over 50 years. It has factions, bad actors, controversies, disputes and feuds. But at the heart of it is the ritual of sitting together. So how do I, as an artist who wants to play with this space’s potential, make that accessible to the uninitiated? I have created a suite of games that approach different spaces, where the people playing are drawn through the rules as they play, as they build a world together, agreeing on their shared parameters, and setting their own boundaries. But the game helps them to discover what happens next, as it leads them through to an end. And one tool in creating that sense of openness and possibility, is to lean into sci fi, the scifi of Ursula Le Guin, Octavia Butler and Philip K Dick.

Haraway again: “SF is storytelling and fact telling; it is the patterning of possible worlds and possible times, material-semiotic worlds, gone, here, and yet to come.”

What this does is to move the gamespace away from a built world, from a pre-made world with lore and history that you have to learn, imposed from above, from World building, to a generative process of making, to Worlding.

Haraway for the final time. She really is great.

“Companion species are engaged in the old art of terraforming; they are the players in the sf equation that describes Terrapolis. Finished once and for all with Kantian globalizing cosmopolitics and grumpy human-exceptionalist Heideggerian worlding, Terrapolis is a mongrel word composted with a mycorrhiza of Greek and Latin rootlets and their symbionts. Never poor in world, Terrapolis exists in the sf web of always-too-much connection, where response-ability must be cobbled together, not in the existentialist and bond-less, lonely, Man-making gap theorized by Heidegger and his followers. Terrapolis is rich in world, inoculated against posthumanism but rich in com-post, inoculated against human exceptionalism but rich in humus, ripe for multispecies storytelling. This Terrapolis is not the home world for the human as Homo, that ever parabolic, re- and de-tumescing, phallic self-image of the same; but for the human that is transmogrified in etymological Indo-European sleight of tongue into guman, that worker of and in the soil.”

‘The World After’ was a film, installation and game.‘The World After’ is a fictional tale which imagines a world after the Anthropocene era, a time in which humanity’s activities had detrimental effect on earth’s climate and environment. In this future world, human influence on the planet has faded following a catastrophic man-made ecological crisis, with those who remain having to find new ways to survive and form kin. The project took inspiration from the unique post-industrial setting of Canvey Wick on Canvey Island, Essex. Formerly the site of an oil refinery that was only partially built in the early 1970s and never operational due to the oil crisis of 1973, Canvey Wick has for the past forty years been reclaimed by nature. I worked with a dedicated group of gamers from the area to create our own game, with our own stories about this mythic future. Inspired by nature’s return, we imagined returning to the surface as posthuman creatures, escaping vast underground silos to see this new world.

The book was beautiful, and was a good first attempt at working in this space, but I was dissatisfied by certain aspects of the game- primarily it was too difficult to learn, and the world was too static, too much based on lore.

So for my next collaborative project, LOST EONS, I wanted to try to make the game more open as a space, and simpler to play. Made in the middle of lockdown with the community around Cambridge, we thought about the consequences of climate change, particularly sea rise, everyone generating self-portraits projected into a far-distant time, where humans have adapted and merged with the area’s flora and fauna. These new characters then developed new myths, with maps, legendary figures and illustrations. The project will formed a future anthropology of the site, a site where our present became their archaeology. The game sits within the world of the independent TTRPG space, using lessons from FKR "Free Kriegspiel Renaissance/Revival/Roleplay" and freeform prompt-based play. But it still required an initiate to lead a group. And that’s what I wanted to solve with Gathering Storm.

Gathering Storm explored my familial link to colonial food production, and the legacy of agriculture as a tool to consolidate authority. My grandfather was involved in the Swynnerton Plan, a British colonial scheme initiated in the 1950s with the aim of creating an African middle class in Kenya: a form of social engineering through agriculture. I developed this tabletop game as a means to embark on a collaborative exploration of my research around the legacies of this era, looking into the archives and reading fiction from the era, particularly Ngugi Wa Thiongo’s A grain of Wheat. I was on a residency at Delfina Foundation, and used the time to test early prototypes with my co-residents and the public, which fed into the game’s development.

The game invites players to take it in turns to add elements to a map, imagining a post-colonial sci-fi world. They then creating a set of characters to inhabit this space. They then respond to prompts, coming to terms with hidden histories and present injustices. The colonial situation in Kenya is transposed to an alien planet, an indigenous people that the table creates having lived through life under a now-gone Authority.

A quote from the game:

“Our planet was occupied by an alien force, who brought their customs, rules and an alien fruit. After years of resistance, the occupation has ended, but they’ve left behind this fruit, and everyone holds a secret from those difficult times.”

Every player takes on a randomly assigned role and randomly assigned secret, and this generates surprisingly rounded characters, but more importantly brings each player psychically into the space, helps them invest in the fiction. Tabletop roleplay is very powerful when properly activated, helping people enter into other spaces. TTRPGs can help us understand other lives, and other ways of living, a speculative fiction we can enter into through the ritual of telling stories and rolling dice. The memories I’ve formed from campaigns feel just as emotionally real as things that have happened to me in life. And they’re memories that you share with everyone else around that table with you.

I tried adapting Gathering Storm, into another, more intimate space. Alien Pastoral: The Strain centres on a biological research station, run by an Authority, as the scientists try to engineer a new strain to solve an existential problem. This game explores the strange and often blurred spaces between agriculture, technology and capitalism. Players collaboratively design a research station complete with seedbeds, orchards and laboratories to experience how relationships change with their environments. Where Gathering Storm took you into a post-colonial community, trying to help you understand the psychological complexities of that space, of lives marked by history, The Strain uses the tropes of sci-fi horror to introduce the possibilities of non-human consciousness. What makes us human, and could we let it go?

Finally, I’ll talk about my most recent game DIACHRONIC: Salvage the Past. This game considers our relationship to the past and its stories, who has access to that past and who writes that history. You play as a time traveller, an Envoy, who has a mission to retrieve artefacts in time periods before a future Explorer has a chance to destroy or pillage them.

Through a series of prompts, the players construct a vivid world in flux, constantly under threat of collapse, as future catastrophe undermines this fragile time shift. Based on the history of Hisarlik and the city of Troy and the ultimately destructive archaeology of Heinrich Schliemann, the game asks the players to consider what has been lost, and how we build new narratives.

Diachronic is a linguistic term concerned with the way in which something, especially language, has developed and evolved through time, but I applied it here to the space of the site itself. Troy underwent a series of radical changes, layers of history lying on top of each other. And part of Schliemann’s legacy was his ignorance about these layers, his destruction of whole swathes as he tried to reach his grail, the Troy of the Homer.

The game uses Tarot, to play with the card’s associative possibilities, and invites players to enter into a generative exploration, seeking to discover aspects of the past, a ritualised act of creating memories, through writing and drawing. I wanted people to feel as though they had truly entered into another time for a moment, like the protagonist in Chris Marker’s La Jetee.

In many ways my games are essays, attempts, sketches about particular places and particular times. Recently I’ve become more and more interested in the possibilities of the adventure module, of a particular narrative seed that can go in all sorts of directions. I’ve been really inspired by Evey Lockhart’s Wet Grandpa and Luke Gearing’s The Isle. Modules are going to be my main focus this year. I want to delve further into the world of ECO MOFOS!!, the game that built on the ideas of LOST EONS through meshing that world with the systems of Into the Odd and Cairn.